The Laugh of the Medusa is a feminist essay written by Hélène Cixous, a prominent French feminist theorist, philosopher, and writer. Originally published in 1975, the text has become a foundational piece of second-wave feminist literature and post-structuralist thought. Cixous was a leading figure in the feminist movement in France during the late 20th century and was instrumental in developing French feminist theory. In ‘The Laugh of the Medusa,’ Cixous passionately challenges the patriarchal constructs that have historically silenced and oppressed women. She encourages women to embrace their bodies, desires, and voices, asserting that their unique perspective can lead to a radical transformation of language and society.

The Laugh of the Medusa | Summary and Themes

The main theme of the text revolves around empowering women through writing and self-expression. Cixous argues that women must write about themselves and their experiences, breaking away from the male-dominated cultural norms that have oppressed and silenced them throughout history. She emphasizes the need for women to reclaim their bodies, desires, and voices, expressing their unique individuality and creativity. Cixous acknowledges that women have been suppressed and made to feel ashamed of their strengths and desires, but she encourages them to overcome these societal pressures and fearlessly embrace their own writing. Furthermore, she highlights the importance of women reclaiming their childhood experiences and embracing their desires, which have been stifled by a phallocentric society. Women should no longer be confined to traditional roles and expectations but should explore and express their desires, whether through writing or other artistic forms.

Hélène Cixous further explores the oppression faced by women and the need for them to liberate themselves through writing and self-expression. She criticizes the way women have been conditioned to fear the dark and to hate themselves, perpetuating an ‘antilove’ logic imposed upon them by men. Cixous celebrates the strength and beauty of women, describing them as stormy, limitless, and unafraid. She emphasizes the importance of women reclaiming their identity and breaking free from the constraints of patriarchal society. The author points out the scarcity of women writers throughout history, attributing it to a male-dominated cultural and literary economy that has perpetuated the repression of women. She argues that even when women have had the opportunity to write, many of their works have conformed to male-centric narratives or stereotypes, failing to truly inscribe femininity. Cixous suggests that writing can be a powerful tool for women to challenge the status quo and effect social and cultural change. She asserts that women must reclaim writing and make it a space for subversive thought, challenging traditional gender roles and the oppressive structures that have marginalized them.

She continues to advocate for women’s liberation through writing and self-expression. She critically examines the history of writing and its association with reason, which she sees as deeply intertwined with phallocentrism, a system that prioritizes male dominance and perspective. The author celebrates the power of women’s speech and writing, describing how women’s voices are often marginalized or dismissed in public gatherings. She urges women to embrace their speech and writing as a form of resistance and a way to challenge patriarchal norms. Cixous also emphasizes the importance of women supporting and empowering each other, creating a sense of solidarity among women. She encourages women to embrace their individuality and desires, free from the constraints imposed by masculine norms. She envisions a new history in which women’s liberation will lead to a transformation of human relations, challenging traditional power dynamics and reshaping societal structures. Cixous acknowledges the difficulty of defining a feminine practice of writing, but she believes it will surpass the limitations imposed by the phallocentric system. She envisions this practice arising from women who break free from established norms and authority, embracing their unique voices and perspectives.

She criticizes the prevailing phallocentric ideology and its suppression of femininity and women’s writing. She explores the concept of bisexuality, not as a merging of sexes but as a multiplicity of desire that embraces and affirms differences. Cixous criticizes the Freudian view that bisexuality is a result of castration fear, arguing that it is a natural state for individuals who reject phallocentric representationalism. She contends that women are benefiting from and embracing this bisexuality, while men are confined to a limited view of masculinity based on the phallus. The author rejects the idea that the feminine sex is unrepresentable, stating that men associate femininity with death to maintain power over women. She advocates for women to reclaim their bodies and sexuality, challenging the shame and modesty imposed on them. Cixous highlights the need for women to write through their bodies, creating a new language that breaks down societal barriers and allows women to express their desires and experiences freely. She emphasizes that women possess immense strength, and through writing, they can liberate themselves from oppressive norms and achieve the impossible. The author urges women to break away from the constraints of patriarchal discourse and embrace the power of their voices and bodies to transform society.

She emphasizes that when the suppressed aspects of culture and society, which include women’s voices and experiences, resurface, it will be a powerful and explosive force that can shatter the oppressive structures. Cixous celebrates women’s resilience and strength, highlighting their fragility and vulnerability alongside their incomparable intensity. She argues that women have not sublimated their desires, but rather inhabited their bodies fiercely, responding to persecution and attempts at subjugation. Women’s writing and language will be more than subversive; it will be volcanic, disrupting the old patriarchal property norms and male-centered language. The author rejects the idea of appropriating men’s instruments and concepts. Instead, she advocates for women to ‘fly’ in language and create their own modes of expression. Women’s capacity to appropriate unselfishly and embrace an ever-changing and cosmic sexuality sets them apart from the centralized and territorialized sexuality associated with the male body. Women’s language, according to Cixous, is boundless and carries the multitude of voices within it. It is not about containment but possibility. She urges women to embrace their alterability, their ability to be multiple and fluid, and to write from within, where they can hear the resonance of the unconscious and the language of the thousand tongues. Women’s writing will know them better than flesh and blood, as it allows them to transform, explore, and express their desires and identities freely. Their language will be heterogeneous, embracing all aspects of themselves, erogenous and capable of reaching out to others and embracing diverse experiences.

Cixous rejects the notion that women desire men’s phalluses to fill a supposed hole or lack within themselves. She challenges the idea that women’s desires revolve solely around the male body or that pregnancy is solely a product of fate or male dominance. Women should have the freedom to choose whether or not to have children and should not be pressured or constrained by societal norms. The author encourages women to embrace their desires for life, pleasure, and creativity, including the desire for pregnancy, which has been tabooed and suppressed in traditional texts. Women should not be reduced to common nouns or categories, but rather they should embrace their uniqueness and individuality.

Cixous criticizes the traditional psychoanalytic approach that often reduces women’s desires to castration complexes or penis envy. She calls for women to break free from the confines of psychoanalytic theory and reclaim their bodies and desires without being subjected to diagnostic classifications. Women should embrace the otherness within themselves and within each other, rejecting the model of competition and hierarchy that has been imposed on them. They should explore love and desire in new ways, beyond selfish narcissism, hierarchy, or possessiveness. Women should seek genuine connection and exchange with others, celebrating the diversity and multiplicity of desires. Ultimately, Cixous encourages women to embrace the history of life rather than the history of death which has been dominated by phallic values. Women’s love and desire should be transformative and life-giving, liberating them from old concepts of management and economics. In each other, they will find infinite possibilities for love and growth.

Cixous rejects the notion that women desire men’s phalluses to fill a supposed hole The author’s message is a call for women to reject the patriarchal structures that have oppressed them and to reclaim their bodies, desires, and creativity. Women’s liberation lies in embracing their own unique experiences and desires, fostering connections with others, and finding joy and fulfillment in the pursuit of life and love.

The Laugh of the Medusa | Socio-Historical Context

The text ‘The Laugh of the Medusa’ by Hélène Cixous is considered a crucial work of French feminism and is deeply relevant to the context of the French feminist movement and theoretical concerns related to post-structuralism and psychoanalysis. French feminism, often associated with the second wave of feminism, emerged in France during the late 20th century and contributed significantly to feminist theory and activism. The text vehemently rejects the phallogocentric (male-centered) discourse that has dominated Western thought for centuries. French feminists, including Cixous, challenged the traditional male-centric language and writing, which they believed suppressed women’s voices and perspectives. Cixous introduces the concept of ‘écriture féminine’ or feminine writing, which emphasizes the unique qualities of women’s writing and expression. This form of writing is fluid, imaginative, and associative, breaking away from the linear and logical style typically associated with male-authored texts.

French feminism emphasized the celebration of sexual differences rather than attempting to assimilate women into male norms. The text encourages women to embrace their own bodies, experiences, and desires without conforming to societal expectations. French feminists challenged the objectification of women and emphasized the importance of women’s subjectivity and sensuality. The text celebrates the sensuousness of women’s bodies and urges women to reclaim their own desires and pleasures. French feminists, including Cixous, believed that writing could be an empowering and liberating act for women. Writing offered a space for women to express themselves, challenge patriarchal norms, and create a new language that reflects their experiences. It placed a significant emphasis on literature and language as important sites of feminist exploration. The text encourages women to reclaim language, using it to articulate their experiences and express their desires.

The text is also deeply influenced by post-structuralist ideas, particularly those of Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault. Post-structuralism emerged as a philosophical and theoretical movement in France during the mid-20th century and had a significant impact on various fields, including literary theory and feminism. Post-structuralism, as developed by Jacques Derrida, emphasizes the deconstruction of binary oppositions and hierarchical structures that dominate traditional Western thought. In ‘The Laugh of the Medusa,’ Cixous seeks to dismantle phallogocentrism, the male-centered discourse that places masculinity at the center and positions femininity as its Other. She challenges this binary by advocating for feminine writing that disrupts conventional hierarchies and creates new meanings. Post-structuralists, including Derrida, were also interested in how language constructs meaning and how representation shapes our understanding of the world. Cixous engages with these ideas by critiquing the language of patriarchy and the way it has marginalized and silenced women. She calls for a new language that breaks free from the constraints of phallogocentrism and allows women to articulate their experiences on their own terms.

Cixous’ text challenges essentialist views of womanhood and instead celebrates the diversity and fluidity of women’s subjectivity. She rejects the idea of a universal ‘woman’ and encourages women to embrace their unique identities and experiences. Additionally, Post-structuralists, such as Foucault, were interested in power dynamics and the construction of ‘otherness.’ Cixous’ text addresses the marginalization of women as the Other within a phallogocentric society. She encourages women to reclaim their own bodies, desires, and voices, thus challenging the status of women as the passive object of male desire. Post-structuralism emphasizes the fragmented and multifaceted nature of language and identity.

Cixous’ writing style in the text reflects this fragmentation, as she employs a poetic and associative language that resists linear narratives. This style allows for a multiplicity of meanings and interpretations, breaking away from the fixed and predetermined meanings of traditional patriarchal discourse. Therefore such theories also question the authority of the author and the stability of meaning in texts. Cixous’ text challenges the authoritative voice of patriarchal discourse and instead offers a multiplicity of voices and perspectives, including those of women. She encourages women to find their own voices through writing, thus destabilizing the dominant male-authored narratives.

As most concepts and ideas are biased against women and are socially and culturally constructed by male hegemony to keep women in a constant state of subordination, these French feminists, like Cixous, used and critiqued psychoanalytic theories to question and challenge male hegemony. French feminists placed a strong emphasis on how women’s physiology may support and direct women’s writing in order to help it break free from the limitations of patriarchal views. Following this line of thought, Cixous vehemently criticizes the masculine phallocentric values represented by Freud and Lacan, accusing them of using the new breed of contemporary woman to satisfy their own sexual demands while simultaneously putting her in a subordinate and demeaning position.

Freud has been criticized by feminists, including Cixous, if we look at his view of sexual differences, which puts man in a superior position for biological reasons. Although Cixous bases much of her theoretical work on psychoanalysis, specifically Freud’s, she uses this latter’s critique of gender roles and developmental theory—which are based on the biological distinctions between men and women—as a counterargument to claim that, despite sexual differences, women should be treated equally and not in terms of Lacanian binary oppositions. Lacan’s idea of phallocentrism, which places the phallus at the center of the masculine being, is also criticized by Cixous.

The Laugh of the Medusa | Literary Devices

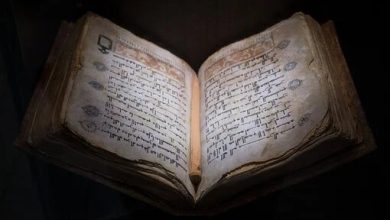

The Laugh of the Medusa is the most important illustration of Cixous’s ‘feminine writing.’The term ‘écriture féminine,’ or ‘feminine writing,’ is coined by Cixous. In her essay The Laugh of Medusa, Cixous challenges the patriarchal rule by interpreting Greek mythology through psychoanalysis, which was influenced by the above-mentioned work of Lacan. We see Cixous’s rebellion against the restrictions placed on women by patriarchy in this work, which is written in the form of poetry. Cixous wants to break the structural norms of logic and argumentation established by patriarchy and instead prefers a poetic medium that is more imaginative and isn’t constrained by the rules of prosaic logic. Through this work, Cixous encourages women to write extensively because it is the platform that can change history and challenge the male hegemony that has kept them out of such art and subjugated them.

She alludes to the figure of Medusa to argue that patriarchal men have distorted the Greek myth of the monster Medusa to portray women who have desires as dangerous and ugly, in contrast to the beautiful, obedient, and virgin princess that they adore. Medusa is portrayed as a fierce, ugly woman who is full of rage and has snakes instead of hair on her head. Cixous urges women to have a rebellious nature that rejects any restrictions or structures placed on them by the patriarchal system. In addition, Cixous uses the metaphor of the laugh of Medusa to challenge the fundamental notion of truth and the deeply established binary thinking of Western patriarchy. Medusa is not just lethal, she is gorgeous and giggling. This laugh is a defiant woman’s laugh against any kind of male authority.

When Cixous approaches Dora directly, she alludes to the tale of a degraded young woman who was used by her father as a piece in a sexual game between him and his mistress’s husband, and subsequently by Freud’s therapy who attempted to persuade her that playing the game was necessary. As a result, the girl experienced double oppression—first from her father and then from Freud. Even if the example of Dora in the essay relates to patriarchal ideology and the suppression of women’s voices, it succeeds in dismantling Freudian notions of male supremacy. Cixous uses the name Dora as a symbol of the feminist struggle rather than simply the psychological harm brought on by masculine domination.