The Boy Who Painted Christ Black

John Henrik Clarke

He was the smartest boy in Muskogee County School – for colored children. Everybody even remotely connected with the school knew this. The teacher always pronounced his name with profound gusto as she pointed him out as the ideal student. Once I heard her say: “If he were white he might someday, become President.” Only Aaron Crawford wasn’t white; quite the contrary. His skin was so solid black that it glowed, reflecting an inner virtue that was strange, and beyond my comprehension.

To read the Summary and Analysis of The Boy Who Painted Christ Black, click here.

In many way he looked like something that was awkwardly put together. Both his nose and his lips seemed a trifle too large for his face. To say he was ugly would be unjust and to say he was handsome would be gross exaggeration. Truthfully, I could never make up my mind about him. Sometimes he looked like something out of a book of ancient history…looked as if he was left over from that magnificent era before the machine age came and marred the earth’s natural beauty.

His great variety of talent often startled the teachers. This caused is classmates to look upon him with a mixed feeling of awe and envy.

Before Thanksgiving, he always drew turkeys and pumpkins on the blackboard. On George Washington’s birthday, he drew large American flags surrounded by little hatchets. It was these small masterpieces that made him the most talked-about colored boy in Columbus, Georgia. The Negro principal of the Muskogee County School said that he would someday be a great painter, like Henry O. Tanner.

For the teacher’s birthday, which fell on a day about a week before commencement, Aaron Crawford painted the picture that caused uproar, and a turning point, at the Muskogee County School. The moment he entered the room that morning, all eyes fell on him. Besides his torn book holder, he was carrying a large-framed concern wrapped in old newspapers. As he went to his seat, the teacher’s eyes followed his every motion, a curious wonderment mirrored in them conflicting with the half-smile that wreathed her face.

Aaron put his books down, then smiling broadly, advanced toward the teacher’s desk. His alert eyes were so bright with joy that they were almost frightening…Temporarily, there was no other sound in the room.

Aaron stared questioningly at her and she moved her hand back to the present cautiously, as if it were a living thing with vicious characteristics. I am sure it was the one thing she least expected.

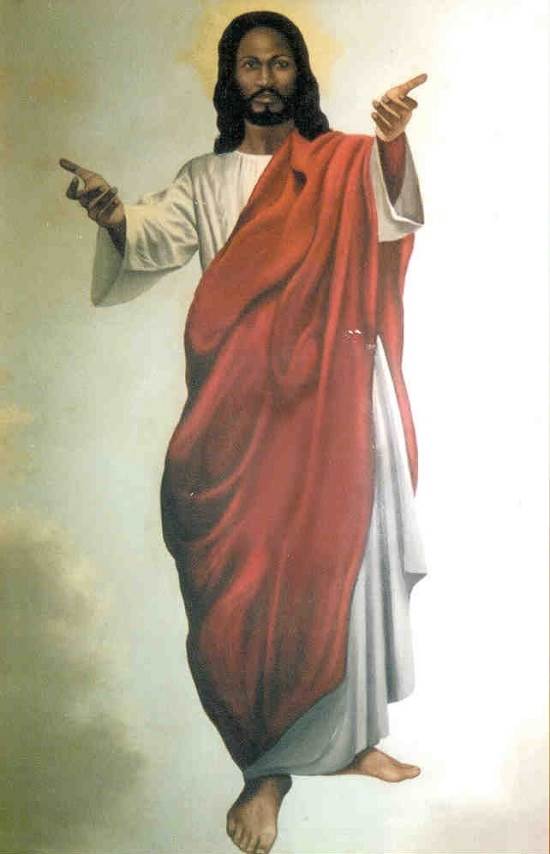

With a quick, involuntary movement I rose up from my desk. A series of submerged murmurs spread through the room rising to a distinct monotone. The teacher turned toward the children, staring reproachfully. They did not move their eyes from the present that Aaron had brought her…It was a large picture of Christ – painted black!

Aaron Crawford went back to his seat, a feeling of triumph reflecting in his every movement.

The teacher faced us. Her cautious half-smile had blurred into a mild bewilderment. She searched the bright faces before her and started to smile again, occasionally stealing quick glances at the large picture propped on her desk, as though doing so were forbidden amusement.

“Aaron,” she spoke at last, a slight tinge of uncertainty in her tone, “this is a most welcome present. Thanks. I will treasure it.” She paused, then went on speaking, a trifle more coherent than before. “Looks like you are going to be quite an artist…Suppose you come forward and tell the class how you came to paint this remarkable picture.”

When he rose to speak, to explain about the picture, a hush fell tightly over the room, and the children gave him all of their attention…something they rarely did for the teacher. He did not speak at first; he just stood there in front of the room, toying absently with his hands, observing his audience carefully, like a great concert artist.

“It was like this,” he said, placing full emphasis on every word. “You see, my uncle who lives in New York teaches classes in Negro History at the Y.M.C.A. When he visited us last year he was telling me about the many great black folks who have made history. He said black folks were once the most powerful people on earth. When I asked him about Christ, he said no one ever proved whether he was black or white. Somehow a feeling came over me that he was a black man, ‘cause he was so kind and forgiving, kinder than I have ever seen white people be. So, when I painted his picture I couldn’t help but pain t it as I thought it was.”

After this, the little artist sat down, smiling broadly, as if he had gained entrance to a great storehouse of knowledge that ordinary people could neither acquire nor comprehend.

The teacher, knowing nothing else to do under prevailing circumstances, invited the children to rise from their seats and come forward so they could get a complete view of Aaron’s unique piece of art.

When I came close to the picture, I noticed it was painted with the kind of paint you get in the five and ten cents stores. Its shape was blurred slightly, as if someone had jarred the frame before the paint had time to dry. The eyes of Christ were deep-set and sad, very much like those of Aaron’s father, who was a deacon in the local Baptist Church. This picture of Christ looked much different from the one I saw hanging on the wall when I was in Sunday school. It looked more like a helpless Negro, pleading silently for mercy.

For the next few days, there was much talk about Aaron’s picture. The school term ended the following week and Aaron’s picture, along with the best handwork done by the students that year, was on the display in the assembly room. Naturally, Aaron’s picture graced the place of honour.

There was no book work to be done on commencement day, and joy was rampant among the children. The girls in their brightly colored dresses gave the school the delightful air of Spring awakening.

In the middle of the day all the children were gathered in the small assembly. On this day we were always favored with a visit from a man whom all the teachers spoke of with mixed esteem and fear. Professor Danual, they called him, and they always pronounced his name with reverence. He was supervisor of all the city schools, including those small and poorly equipped ones set aside for colored children.

The great man arrived at the end of our commencement exercises. On seeing him enter the hall, the children rose, bowed courteously, and sat down again, their eyes examining him as if he were a circus freak.

He was a tall white man with solid-grey hair that made his lean face seem paler than it actually was. His eyes were the clearest blue I have ever seen. They were the only lifelike things about him.

As he made his way to the front of the room the Negro principal, George Du Vaul, was walking ahead of him, cautiously preventing anything from getting in his way. As he passed me, I heard the teachers, frightened, sucking in their breath, felt the tension tightening.

A large chair was in the center of the rostrum. It had been daintily polished and the janitor had laboriously re-cushioned its bottom. The supervisor went straight to it without being guided, knowing that this pretty splendor was reserved for him.

Presently the Negro principal introduced the distinguished guest and he favored us with a short speech. It wasn’t a very important speech. Almost at the end of it, I remembered him saying something about he wouldn’t be surprised if one of us boys grew up to be a great colored man, like Booker T. Washington.

After he sat down, the school choir sang two spirituals and the girls in the fourth grade did an Indian folk dance. This brought the commencement program to an end.

After this the supervisor came down from the rostrum, his eyes tinged with curiosity, and began to view the array of handwork on display in front of the chapel.

Suddenly his face underwent a strange rejuvenation. His clear blue eyes flickered in astonishment. He was looking at Aaron Crawford’s picture of Christ. Mechanically he moved his stooped form closer to the picture and stood gazing fixedly at it, curious and undecided, as though it were a dangerous animal that would rise any moment and spread destruction.

We waited tensely for his next movement. The silence was almost suffocating. At last he twisted himself around and began to search the grim faces before him. The fiery glitter of his eyes abated slightly as they rested on the Negro principal, protestingly.

“Who painted this sacrilegious nonsense?” he demanded sharply.

“I painted it, sir.” These were Aaron’s words, spoken hesitantly. He wetted his lips timidly and looked up at the supervisor, his eyes voicing a sad plea for understanding.

He spoke again, this time more coherently. “Th’ principal said a colored person have jes as much right paintin’ Jesus black as a white person have paintin’ him white. And he says…” At this point he halted abruptly, as if to search for his next words. A strong tinge of bewilderment dimmed the glow of his solid black face. He stammered out a few more words, and then stopped again.

The supervisor strode a few steps toward him. At last color had swelled some of the lifelessness out of his lean face.

“Well, go on!” he said enragedly, “…I’m still listening.”

Aaron moved his lips pathetically but no words passed them. His eyes wandered around the room, resting finally, with an air of hope, on the face of the Negro principal. After a moment, he jerked his face in another direction, regretfully, as if something he had said had betrayed an understanding between him and the principal.

Presently the principal stepped forward to defend the school’s prized student. “I encouraged the boy in painting that picture,” he said firmly. “And it was with my permission that he brought the picture into this school. I don’t think the boy is so far wrong in painting Christ black. The artists of all other races have painted whatever God they worship to resemble themselves. I see no reason why we should be immune from that privilege. After all, Christ was born in that part of the world that had always been predominantly populated by colored people. There is a strong possibility that he could have been a Negro.”

But for the monotonous lull of heavy breathing, I would have sworn that his words had frozen everyone in the hall. I had never heard the little principal speak so boldly to anyone, black or white.

The supervisor swallowed dumb-foundedly. His face was aglow in silent rage.

“Have you been teaching these children things like that?” He asked the Negro principal, sternly.

“I have been teaching them that their race has produced great kings and queens as well as slaves and serfs,” the principal said. “The time is long overdue when we should let the world know that we erected and enjoyed the benefits of a splendid civilization long before the people of Europe had written a language.”

The supervisor shook with anger as he spoke. “You are not being paid to teach such things in this school, and I am demanding your resignation for overstepping your limit as a principl.”

George Du Vaul did not speak. A strong quiver swept over his sullen face. He revolved himself slowly and walked out of the room towards his office…

Some of the teachers followed the principal out of the chapel, leaving the crestfallen children restless and in a quandary about what to do next. Finally we started back to our rooms.

A few days later I heard that the principal had accepted a summer job as art instructor of a small high school somewhere in South Georgia and had gotten permission from Aaron’s parents to take him along so he could continue to encourage him in his painting.

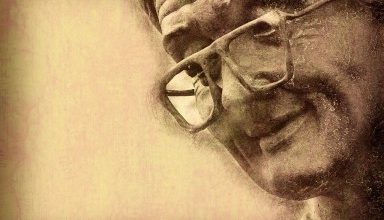

I was on my way home when I saw him leaving his office. He was carrying a large briefcase and some books tucked under his arm. He has already said good-by to all the teachers, and strangely, he did not look broken-hearted. As he headed for the large front door, he readjusted his horn-rimmed glasses, but did not look back. An air of triumph gave more dignity to his soldierly stride. He had the appearance of a man who had done a great thing, something greater than any ordinary man would do.

Aaron Crawford was waiting outside for him. They walked down the street together. He put his arms around Aaron’s shoulder affectionately. He was talking sincerely to Aaron about something, and Aaron was listening, deeply earnest. I watched them until they were so far down the street that their forms had begun to blur. Even from this distance I could see they were still walking in brisk, dignified strides, like two people who had won some sort of victory.

A very compact short story depicting racial prejudice by the supervisor against the principal and the young learner Aaron. In the face of this hatred the duo appear indefatigable. The principal stands his ground and defends humanitarian liberty at the expense of losing his job. Ironically, the supervisor cannot defend his racial superiority when the principal confronts him with true facts of civilization that it was the black man that started writing before the whites claimed false history.