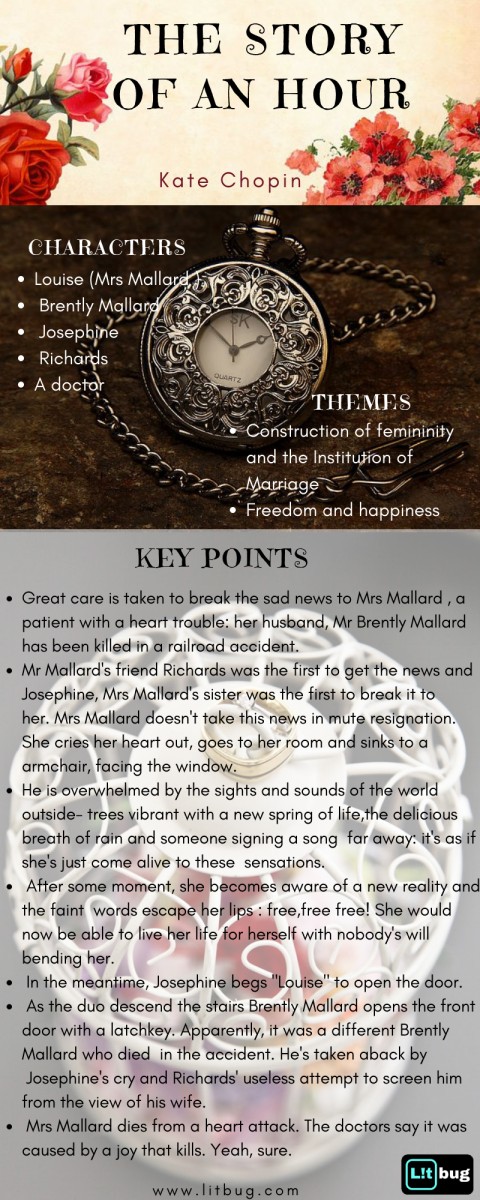

The Story of an Hour : The Story

The Story of an Hour, originally titled The Dream of an Hour by Kate Chopin concerns a curious episode in the life of a woman who has just heard the news of her husband’s death and who comes to terms with the consequences arising thereof. Blasting off gender stereotypes in a frank and honest manner, this story brings up some disconcerting issues and raises some important questions around the construction of femininity and the institution of marriage.

Got No Time? Check out this Quick Revision by Litbug

The Story of an Hour : Summary

Mrs Mallard, the protagonist of the story isn’t satisfied with her marriage to Brently Mallard. Some important facts are presented right at the outset of the story : that Mrs Mallard is afflicted with a heart disease and that her husband has just been killed in a railroad accident. Her sister Josephine and her husband’s friend Richards are the first (and the last) give her the sad news. Richards had in fact been the first to receive the telegram notifying Mr Mallards’s death. He rushes to the house with the motive of relating her the news in as gentle a manner as possible. Finally, it’s Josephine who breaks the news.

Instead of giving in to mute resignation, Mrs Mallard cries her heart out, locks herself in her room and sinks into an armchair. She takes some time to recover composure before stumbling upon an important realisation – that she is free from her husband’s command and henceforth can become the mistress of her own life. At first, she comes across a feeling “too subtle and elusive to name“. She even tries to fight it back for sometime before the words finally escape her lips ” free, free free!”. Her eyes lose the vacant stare of terror and instead turn “keen and bright”. We then witness her breaking free from the socially constructed role of the dutiful wife. It is a moment of epiphany. A highly sensory language is used to describe the intensity of her feelings. It’s as if she’s just come alive to the experiences around her:

She could see in the open so hard before her house the tops of trees that were all aquiver with the new spring life… There would be no one to live for her during those coming years; she would live for herself.

It seems as if she was living her life for somebody else all this time. The fact that it is her husband’s death which brings her alive to all the happenings around her is quite telling. Mrs Mallard begins to feel that the feeling of “love” isn’t in fact as powerful as the possession of self assertion.

Meanwhile, her sister Josephine is standing at the door, pleading her sister to open it. Louise‘s ( No more Mrs Mallard now) joy over this newfound freedom is so complete that she almost gives herself away when she gives in to her sister’s request and comes out of the room carrying herself unwittingly “like a goddess of Victory.” However, her joy turns out to be a short-lived one and her freedom remains unrealized when Mr Mallard enters the house. Turns out, it was a different Brently Mallard who was killed in the railroad accident. Being afflicted with a heart trouble and with all her dreams dashed at the unfortunate sight of her healthy husband, Lousia gets a heart stroke and dies.

The Story of an Hour : Analysis

The Story of an Hour is what it says: it is the story of an hour in the life of a married woman. However, this hour is unlike any she has been through so far. It is in this hour that she, on hearing about her husband’s ‘death’ discovers her freedom. Spanning a great length of barely three pages, the well-crafted story is a strong feminist critique of the society, the institution of marriage and the construction of femininity within that institution. Furthermore, it is also a critique of the (mis)representation and misinterpretation of women in art and literature. Female self-assertion, independence and freedom lie at the core of this short story. Chopin’s intense engagement with the feminist cause is central to understanding the story which has been hailed as one of the foremost examples of feminist fiction in the short story form.

Chopin’s construction of the plot, the protagonist and her use of language demands undivided attention if one is to make a sound analysis of this story.

Mrs Mallard is introduced as an unhappy housewife with a heart trouble. The mention of her heart condition right at the beginning of the story is significant and will be taken up later in the course of analysis.

The well-wishers of Mrs Mallard try to soften the blow of her husband’s death as carefully as possible. Her sister tries to convey the message “in broken sentences; veiled hints that revealed in half concealing”. Her husband’s friend Richards hurries himself to the spot to prevent “any less careful, less tender friend in bearing the sad message“. Though it is true that her heart trouble necessitated such precautions, it is safe to assume that the manner of informing her about her husband’s death would’ve been just as covert even if she did not have a heart trouble. The most obvious reason for such a cautionary move is the blow inflicted by a dear one’s death. The not-so-obvious reason is that women in the past have been constructed as delicate people when it comes to handling such situations. Years of construction of feminity by male writers and the reiteration of gender stereotypes in literature has led to the creation of certain behavioural ‘expectations’ from the female character. This is perhaps what Kate Chopin is consciously writing against. Consider the first line of the third stanza of the story:

“She did not hear the story as many women have heard the same, with a paralyzed inability to accept its significance”

Which women is the speaker talking about? The women in real life or the women in fiction, or both? Chopin is keenly aware of the gender stereotypes engendered by years of male-centered literature. Perhaps she is also aware of the stereotypes being shared by the reader. It is this consciousness about the tradition of writing preceding her and the reworking of that tradition which makes The Story of an Hour not just a story of an hour but a response to the Stories of the Ages which had established the ‘norm’ through literary repetition.

A ‘storm of grief‘ overwhelms Mrs Mallard on hearing of her husband’s death. After the storm subsides, she goes to her room and becomes aware of the new possibilities her life can take following her husband’s death.

One might be tempted to dismiss Mrs Mallard as a selfish person. However, she isn’t an unfeeling individual. We are told that “she knew that she would weep again when she saw the kind tender hands folded in death”. She isn’t happy that her husband died. She’s happy that she is free. There’s a difference between the two. The unrealistic societal expectations asking women to feel in this way and not that, to react in one way and not another has been reinforced by a huge portion of literature to such an extent that the female figure has frequently been either deified or demonized and often been denied a fair treatment on human terms. When given due consideration, we find that the seeming ‘selfishness’ of Mrs Mallard is no more than a very basic human aspiration: to be seen and be treated as a free human being. And it isn’t just about women the speaker is concerned with. We are given to understand she is against the “blind persistence with which men and women believe they have a right to impose a private will upon a fellow-creature. ”

Neither is it the case that their’s is a loveless marriage or that Mr Mallard is a bad husband. We are told that Brently’s was a “face that had never looked save with love upon her“. But perhaps love isn’t enough. Perhaps it is the institution of marriage itself which results in unequal power relation between either parties which further leads to one’s will being suppressed by another, no matter how benevolent the partner may be. By locating the suffocation faced by Mrs Mallard within the structure of a relatively good marriage, Chopin locates the problem in the structure itself and leaves no room to point at Mrs Mallard’s situation as a strictly subjective case.

A rich symbolism is employed in the scene where Mrs Mallard shuts herself in a room after hearing of her husband’s death where she leans against an open window:

The delicious breath of rain was in the air. In the street below a peddler was crying his wares. The notes of a distant song which someone was singing reached her faintly, and countless sparrows were twittering in the eaves. There were patches of blue sky showing here and there through the clouds that had met and piled one above the other in the west facing her window.

This heavily sensory imagery, completely engulfing the visual, the aural and the olfactory seethes with a newfound desire for life. It is as if she has been reborn. Moving beyond the literal, the open window is symbolic of the opening of a new life after her husband’s death. The blue sky reflects the freedom she now has and the infinite possibilities her life can now acquire. This is especially the case since the blue sky shows “through the clouds that had met and piled one above the other“, similar to the way in which years of her marriage had subjugated of her will to that of her husband’s and had suffocated her life so far.

Chopin has made a brilliant use of contrast in this story. Mrs Mallard’s death is contrasted with Louise’s newfound life. Notice, that Mr Mallard is supposed to have died in a railroad accident, a casualty of a hard, mechanical machine. Mechanical, like an institution – like the institution of marriage. Louise’s discovery of a new life on the other hand is organic and takes place in the lap of nature where the “trees are aquiver with the new spring life“. This free state of being is natural, unlike the artificial man-made institution of marriage.

Because gender identity has been actively constructed through narratives and acting out of those narratives in real life, the actions of people are often (mis)interpreted by comparing it with a set of “expected” behaviour. This is perhaps one of the reasons why Josephine kneels before the keyhole of the closed door, imploring her sister to open the door saying that “she will make herself ill” and Richard rushes to the scene before any “less careful‘ and ‘less tender‘ person relates the message. However,our Mrs Mallard is beyond any societal ‘expectation’ because she is an individual, a human being and her identity cannot be compartmentalized within the narrow confines of societal norms. It is interesting to note that this is also the first time (and that towards the very end of the story) we get to hear the actual name of the protagonist and not merely by her title and an appendage of her husband. Louise is much more than Mrs Mallard. And that we come to know her real name and identity only after her husband’s supposed death is a telling one indeed.

Here, one may briefly touch upon thecharacter of Josephine, Mrs Mallard’s sister who serves as a foil to the protagonist. Josephine is someone who plays by the narrative insofar as the construction of the female identity is concerned. She expects her sister to react in a certain manner on hearing about her husband’s death and though her behavior may border on sisterly concern, she seems to have internalized the narrative constructed around the idea of a ‘wife’ and fails to anticipate or imagine an alternative mode of behavior on one’s part as opposed to the established ‘traditional’ one.

A close relationship between freedom and happiness is established in Mrs Mallard’s epiphanic moment after her husband’s death. She begins to view freedom as the strongest impulse and a real condition, above the romanticized interpretation of love and marriage. Freedom therefore becomes a necessary condition for happiness:

What could love, the unsolved mystery, count for in the face of this possession of self-assertion which she suddenly recognized as the strongest impulse of her being!

A highly figurative language, rich in similies and metaphors is deployed in this amazingly brief story. The storm of grief makes Mrs Mallard sob like a child before a monstrous joy overwhelms her and her fancy runs riot, making her carry herself like a goddess of Victory. Eventually, she ‘descends‘ the stairs, away from her freedom to death. Quite literally.

Mrs Mallard dies of a heart stroke on seeing her husband alive and kicking. The doctor infers the reason to be a sudden joy on her part – a joy that kills. It is here that the little piece of information about her heart condition furnished in the beginning of the story turns out to be of great value. By citing a genuine physical condition right at the outset, Chopin saves the character of Mrs Mallard from being reduced to a caricature and saves the character of from collapsing into another stereotype.

The importance of ‘truth’ and its interpretation is one of the central concerns of the story. The literary device of foreshadowing is employed to understand the nature of a fact and its interpretation. The problems of interpreting a fact is more importantly seen in two different instances at the opposite ends of the story. In the beginning of the story, the first person to receive the news about Mr Mallard’s death is Richards who waits for a second telegram to confirm the ‘truth’ of the first telegram. This verification and interpretation of ‘truth’ turns out to be a false one. Towards the end of the story, another misinterpretation of an event occurs in that, the reason behind Mrs Mallard’s death as stated by the doctor is equally misleading. The doctor attributes her death to a shock of joy. The readers know better. The truth is obliterated in this case, thanks to the interpretation by an authority figure (the doctor) : quite like many traditional modes of thought and behaviour which amplifies one view and silences another. As in her life, Mrs Mallard has been misinterpreted in her death. And there’s nothing she can do about it, for her final response to the denial of freedom is death.

The Story of An Hour : About the author

Born to a family of French and Irish descent, Kate Chopin was an American novelist and a short story writer who has been widely regarded as one of the foremost American feminist fiction writers.

Chopin’s literary output prior to her marriage was rather negligible. She married a certain Oscar Chopin in 1870. Oscar died in 1882, leaving Kate in a huge debt. Following his demise, Kate also lost her mother and the double tragedy pushed her into depression. A family friend (doctor by profession) suggested her to start writing as a therapeutic exercise. It was then that her literary career slowly began its course.

Chopin wrote numerous short stories and poems, regularly contributing to magazines like The Youth Companion and Vogue among others. Her first novel At Fault wasn’t especially popular but her later collection of short stories established her as a writer of repute. Some of the most important collections of her short stories include Bayou Folk and A Night in Acadia.

The Awakening is generally considered to be her masterpiece where she explores the deepest concerns of a young wife who abandons her family and eventually commits suicide. The book dealt with themes like interracial marriage and female sexuality in a manner which was far ahead of its time.

Her realistic treatment of female characters, clever use of irony and effective diction marked her her as a serious writer of her times and the pages of her literature reflect the first glimpse of feminist thought in fiction. Her short stories like Desiree’s Baby, Regret, Madam Celestinelz Divorce etc explore the most private desires, emotions and aspirations of the female character. Female same-sex desires have been boldly dealt with in works like Lilacs and The Awakening.

A bulk of her oeuvre explore women’s search for identity and selfhood, distinct from the socially constructed rules and their attempts at reconstructing the same according to their own terms. The Story of an Hour is borne of such legacy.

Chopin died in August 28, 1904 following a brain hemorrhage.