Internationally acclaimed, the novel No Longer Human, originally titled Disqualified From Being Human in Japanese, is a semi-autobiographical I-novel penned by the renowned Japanese author Osamu Dazai.

The narrative of No Longer Human, originally titled Ningen Shikkaku in Japanese, delves into the tumultuous life of the protagonist, presented as the fictionalized memoir of Yozo Oba. The story is a semi-autobiographical account of the author’s life and experiences. Through profound self-reflection and compelling storytelling, Dazai examines the intricacies of mental illness and the profound complexities of the human experience.

The novel explores the life of Yozo Oba, a young man who struggles with a profound sense of alienation and despair. From a young age, Yozo finds it difficult to connect with others and conform to societal norms. He hides his true feelings and thoughts behind a facade of humor and eccentricity, making it challenging for anyone to understand the depths of his emotional turmoil. Yozo embarks on a journey of self-destruction, battling addiction, depression, and a sense of purposelessness, ultimately leading him to the brink of suicide. Some themes explored by the novel include alienation, isolation, depression, self-destruction, and deception. At its foundations, No Longer Human is a powerful exploration of the human psyche and the struggles of an individual trying to find their place in a world that seems indifferent and oppressive.

Osamu Dazai, born Shūji Tsushima in Kanagi, Aomori Prefecture, Japan lived from June 19, 1909, to June 13, 1948. He later adopted the pen name Osamu Dazai. Dazai is considered one of the most important figures in modern Japanese literature and is known for his introspective and psychologically complex works. Dazai’s works often explore dark and existential themes, including alienation, depression, and the human condition. His writing frequently delved into the psychological struggles of his characters, mirrored by Dazai’s personal life, which was marked by turmoil, including struggles with mental health, addiction, and a tumultuous family life. Osamu Dazai died by suicide on June 13, 1948, aged thirty-eight.

No Longer Human | Summary

PROLOGUE

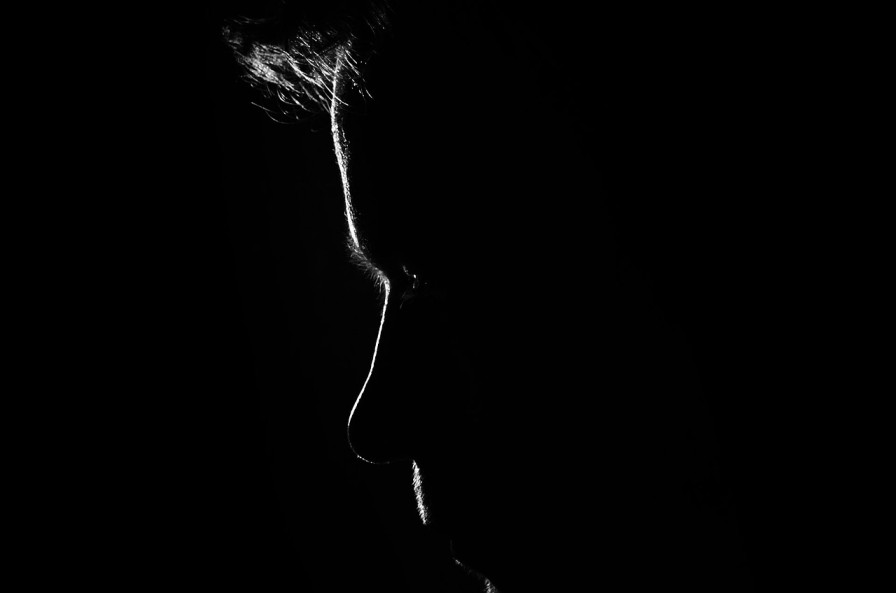

An unnamed narrator presents three images of an individual ambiguously identified as the “man.” The first picture depicts the man during his childhood, and while some might find him exceptionally adorable, the narrator vehemently asserts the boy in the photograph is unattractive – “a wizened, hideous little boy.” The narrator firmly believes that a close examination of the image would unveil that the seemingly cheerful boy is not genuinely smiling. His clenched fists and an underlying sense of unnaturalness pervade his facial expression, despite its initial appearance of joy and charm.

The second snapshot captures the man during his high school or college years. Although “extraordinarily handsome,” his face fails to “give the impression of belonging to a living human being.” Nevertheless, the speaker contends that the ostensibly smiling face lacks substance and the essential “solidity of human life.” A vacancy permeates the visage, one that produces a certain sense of artificiality and pretense.

The third image, the narrator continues, is the most disconcerting of them all, portraying the man as an adult within a squalid room. On this occasion, his face bears no expression whatsoever—so utterly devoid that one would struggle to retain a mental image of it even moments after viewing the photograph. There exists no distinguishing or individualistic aspect to the man’s expression, and has a “chilling, foreboding quality, as if it caught him in the act of dying.” It is a profoundly unsettling experience, marked by an indescribable and unknowable quality that renders the man’s appearance profoundly unfamiliar.

The First Notebook – Summary

The perspective shifts, and in the first person, a different voice in the narrative confesses to leading a life filled with shame. The voice confesses that it cannot even imagine how it must be to “live the life of a human being.” Every day things appear foreign and bewildering to him. In his childhood, for instance, he struggled to comprehend the purpose of a station bridge connecting two train platforms, initially perceiving it as a means for people to climb, finding it an elegant and exotic addition to provide diversity to the premises. However, when he eventually grasped its actual function, he was disheartened by what he perceived as banal human understanding. Similarly, he once believed that pillowcases served purely as decorative items, and when he discovered their utilitarian purpose, he felt deeply despondent, considering it an example of human dullness.

The narrator continues to express his profound inability to grasp human emotions. During his childhood hunger was a foreign concept to him; he ate because he recognized it as an expected behavior. He would overindulge to please his family upon returning from school, eating whatever was necessary to satisfy them, but he never experienced a genuine physical need for food.

Furthermore, he narrates that the concept of human happiness remains elusive to him -he has never personally encountered it. He finds it mystifying how others can derive pleasure from life and take interest in the ordinary, whereas he has carried the weight of torment and anguish from the mere existence of his being since childhood, rendering him incapable of appreciating life in any way.

Yozo continues to document his existential dilemmas, tormented by his self-consciousness and alienation, marked by his inability to communicate with or share the same emotional responses as others. To mask his stark differences and blend in, he devises a strategy of deception by engaging in what he calls “clowning.” This involves mastering the art of making people laugh and bringing them joy, despite deriving no personal happiness from it. He becomes remarkably proficient at eliciting laughter from others. Here we are routed back to Yozo’s family photographs (like the ones narrated in the Prologue), wherein he perseveres to maintain always a “peculiar smile,” even amidst his family’s serious faces. Yozo’s motivation for this behavior stems from an intense aversion to the idea of facing criticism or judgment from people, which he generally finds terrifying. Consequently, he resolves to use humor as a shield, reasoning that if people laugh at him, they might pose less of a threat.

Yozo’s “clowning” is not limited to school or public settings; he extends it to his home life and the servants, where he successfully deceives his family members into believing he is a carefree and humorous young boy.

One such encounter had been when his father, about to depart on a business trip, struggled to elicit a response from Yozo regarding a souvenir he could bring back. Despite his father’s suggestion of a lion’s mask, Yozo is unable to articulate any desire. This upsets his father. Yozo’s younger brother intervenes, suggesting to their father that he should choose a book as a gift for Yozo. However, their father appears visibly annoyed and disappointed with this suggestion. Later that evening, Yozo realizes that he should have straightforwardly expressed his desire for the lion mask, as it became evident that his father had intended to give it to him. Later, he covertly slips downstairs, locates his father’s notebook, and inscribes the words “LION MASK” within its pages. Upon his father’s return from the trip, Yozo overhears him conversing with his mother, sharing his delight at discovering “LION MASK” in the notebook. He speculates, in a contented tone, that young Yozo must have desired the lion mask so intensely that shyness prevented him from articulating it.

At school, Yozo excels in his ability to amuse his classmates, even managing to elicit smiles from his teachers, even during moments of misbehavior. He frequently creates amusing cartoons that greatly please his peers. When it comes to homework assignments, he crafts unconventional stories that, while deviating from the assigned topics, ultimately succeed in evoking laughter from his teacher.

However, Yozo’s outwardly “clowning” persona does not align with his internal emotions. He perceives himself as an actor perpetually performing, even in front of his family and their numerous servants. Consequently, he feels a stark dissonance between his outwardly jovial demeanor and his true self. He is sexually abused by the servants in his house and narrates about the profound horror and vileness of subjecting a child to such experiences. Nonetheless, during that period, he chooses to remain silent, enduring the abuse and allowing it to shape his overall perception of humanity. Furthermore, Yozo experiences a profound sense of estrangement from his parents, which prevents him from confiding in them about the sexual abuse he endures from the household servants. His feelings of disconnection from other humans make the idea of sharing his experiences seem insurmountable, as he has no understanding of how they might react. He states the lack of people to confide in; this included his family, the police, and the government. He muses about the possibility of being silenced if he ventured to share the truth, points out the follies of human favoritism, and states his general distrust and lack of faith in human beings.

To exemplify this, he narrates an incident from his childhood when a celebrated figure of the political party his father belonged to had come to the theatre to deliver a speech. After the speech, Yozo had heard his father’s closest friends criticize his opening remarks, but later, when stopping by their house, these very men had applauded his father, “with expressions of genuine delight,” what a success it had been.

As the years pass, Yozo observes that women are often drawn to him, speculating that they perceive him as a man capable of safeguarding their romantic confidences.

The Second Notebook – Summary

Yozo attends high school by the coast while residing with a relative, relishing the distance from his immediate family as it allows him to freely engage in his “clowning” without the burden of familiarity. In this new setting, he skillfully wins the favor of his classmates and teachers through his ability to make them laugh. However, his world is abruptly shaken when he encounters an unsuspecting boy named Takeichi during a physical training exercise at school.

During the exercise, Yozo deliberately fails a physical challenge in a comical, slapstick manner, eliciting laughter from everyone present. Yet, Takeichi, whom Yozo perceives as an unperceptive onlooker, unexpectedly taps him on the shoulder and utters, “You did it on purpose.”

Yozo is deeply disturbed by Takeichi’s words, as they shatter his sense of security and make him feel as if his carefully constructed facade has crumbled. In the ensuing days, he becomes convinced that Takeichi can see through his act, even as he successfully deceives everyone else with his humorous antics. Fearing that Takeichi might expose him as a fraud, Yozo resolves to befriend him closely to win his trust and persuade him that he is not pretending to be a clown. However, forming this bond proved to be more challenging than Yozo anticipated. He is consumed with the idea of keeping a vigilant eye on Takeichi to prevent any revelations, determined to convince him of his authenticity. If this strategy fails, Yozo contemplates the dire possibility of hoping for Takeichi’s demise, although he adamantly insists he would never resort to violence or contemplate murder.

After several attempts, Yozo finally succeeds in befriending Takeichi on a day of heavy rain, by inviting him to his house after school. In Yozo’s room, Takeichi mentions discomfort in his ears, prompting Yozo to examine them. He notices pus oozing from Takeichi’s ears carefully wipes it away, and apologizes for bringing him out in the rain. Yozo adopts a nurturing tone and demeanor, speaking in a manner he typically associates with women, and attempting to act as a caretaker. Eventually, Takeichi appreciates Yozo’s kindness and comments that many women will surely be attracted to him.

Yozo is somewhat perturbed by Takeichi’s remark about women being drawn to him. Looking back, he realizes that Takeichi’s words have been oddly prophetic. Throughout his life, Yozo has found attention from women discomfiting, partially because he finds women even more difficult to understand than men. Nevertheless, women tend to be drawn to him. For instance, while residing in his relative’s house during high school, his two female cousins, who also live there, frequently visit his room. Despite his lack of desire to engage with them, he goes out of his way to make them laugh and strike up conversations.

One day, Takeichi visits Yozo’s house and presents him with a reproduction print of a painting that Yozo recognizes as Van Gogh’s self-portrait. However, Takeichi describes the painting as depicting a ghost. Yozo is astonished and deeply moved by this peculiar interpretation. He begins contemplating how some people perceive the world with a horrified gaze, viewing fellow humans as terrifying “monsters.” To cope with this perspective, some individuals, like many renowned painters, choose not to shrink from the horror and peculiarity of humanity but instead capture it unflinchingly through art. At that moment, Yozo resolves to become a painter.

While Yozo has always enjoyed drawing cartoons, he now decides to courageously portray the grotesque aspects of humanity he encounters. He believes his paintings are horrifying, but they authentically represent his true self. He only shares them with Takeichi, as showing them to others might risk them not recognizing Yozo’s genuine nature in the paintings, which would be mortifying.

Takeichi, on his part, holds the belief that Yozo has the potential to become a great painter. Upon completing high school, Yozo aspires to attend art school, but his father redirects him to a conventional college in Tokyo, aiming to make a civil servant of him. Initially, Yozo lives in the dormitories, but he loathes the company of his fellow students. Consequently, he relocates to his father’s townhouse located nearby.

In due course, Yozo crosses paths with a fellow art student named Masao Horiki, who fashions himself as something of a rebel. Horiki insists on taking Yozo out for drinks, despite Yozo’s initial reservations. However, Yozo experiences the joys of inebriation for the first time, forging a connection between the two young men. Yozo still harbors some dislike for Horiki, who frequently borrows money from him. Nevertheless, he views Horiki as a preferable companion compared to the average person, especially considering that Horiki assists him in navigating the intimidating environment of Tokyo, which had previously intimidated him.

Another reason Yozo develops an affinity for Horiki is the latter’s apparent disregard for others’ opinions. This allows Yozo to comfortably remain in the background while Horiki engages in spirited conversations. As their companionship deepens, Yozo begins to acquire certain habits regarding drinking, smoking, and sleeping with prostitutes. All of these habits give Yozo a sense of escape. Yozo describes his inability to visualize the sex workers he visits as women, or even as human beings. To him, they were “imbeciles” or “lunatics”, but it was only in their company that he felt absolute security – only in their company was he able to sleep soundly, feeling a certain sense of kindness with them. However, upon Horiki’s observation that women seem to be fond of Yozo, owing to the “lady-killer” persona he had developed over time, he is so repulsed by the comment that his desire to visit prostitutes diminishes entirely.

Horiki introduces Yozo to a Communist Party gathering. Yozo initially finds the members both ludicrous and self-important, relishing their earnest discussions on what he considers trivial matters. He begins attending these meetings regularly, not because he genuinely shares their convictions, but because he is amused by their irrationality, in stark contrast to the rigidly logical nature of the broader society. To ease the tension in the room, he reverts to the clownish persona he adopted during his school days, which earns him popularity among the Party members.

Over time, Yozo realizes that his fondness for the Communist Party stems from his enjoyment of the members’ irrationality. It offers him a sense of belonging in a society where he often feels like an outcast. Although he has no true commitment to communism, he relishes the feeling of being part of a clandestine, subversive movement. Consequently, he willingly undertakes covert tasks for the Party, fully aware that some of these missions could lead to his arrest. Strangely, the prospect of a life in prison does not deter him, as it does not seem as bleak as it might to others.

Yozo’s father decides to sell their house in Tokyo as his political term comes to an end. With this change, Yozo realizes that he will have limited financial resources. His father had consistently provided him with a monthly allowance, but he often squandered it on alcohol and cigarettes within a matter of days. While his father lived in the city, Yozo had the privilege of charging his purchases to his father’s account at local stores. However, this option is no longer available to him after moving into his place. As a result, he quickly depletes his monthly allowance and becomes consumed by fear due to his dwindling finances. To make ends meet, he resorts to selling his belongings at pawnshops, yet he still struggles to secure enough money to meet his needs.

During this period, Yozo dedicates the majority of his time to either attending Communist Party meetings or indulging in heavy drinking sessions with Horiki. As a consequence, his academic pursuits and passion for painting both suffer, but he remains apathetic towards these declines.

Also in this tumultuous phase, he finds himself entangled in a tumultuous affair with a married woman, which he describes as a “love suicide.” His absence from classes for an extended period leads to a stern reprimand from his family in a strongly-worded letter. However, Yozo remains unfocused on his studies. His previous amusement in his involvement with the Communist Party wanes, and his sole desire becomes to drink until he reaches a state of complete numbness, although even this pursuit is hindered by his lack of funds. Overwhelmed by a desire to escape from everything, he ultimately decides to kill himself.

Overwhelmed by the weight of depression and life’s burdens, Yozo seeks solace in a bustling café, hoping to blend into the tumultuous scene and lose himself within it. Unfortunately, he lacks the financial means to fully embrace this escape. As soon as he settles in, he openly informs the waitress about his meager financial situation. Surprisingly, she reassures him, pouring him liquor and creating an atmosphere where the specter of money no longer haunts him. Strangely, he finds himself freed from the need to put on his usual public facade in her presence.

Looking back on the encounter with the married woman, who had been a waitress, Yozo struggles to recall her name, even though they once contemplated killing themselves together. Such forgetfulness is not uncommon for him. However, he vividly remembers the poor sushi he had had while waiting for her to finish her shift. He believes her name was Tsuneko and recollects moments spent in her rented apartment, sipping tea as she tells him of her husband, incarcerated for a fraudulent scheme.

As Yozo reclines in her apartment, Tsuneko delves into the intricate details of her life and the multitude of challenges she faces. He listens with only partial attention until her desperate confession of unhappiness captures his full focus. It is then that suddenly, a sense of peace envelops him as he lies alongside her, no longer trapped in a perpetual state of fear and discomfort. In that fleeting moment, he even experiences a rare taste of freedom and happiness, and he acknowledges that this is likely the only instance the word “happiness” will grace his journals. However, upon waking the next morning, the feeling dissipates, and he once again embodies the persona of a superficial clown, bereft of depth.

In the days that follow, Yozo wrestles with a sense of discomfort regarding Tsuneko covering the cost of their drinks at the café. He is concerned that she might resemble the other women who have shown interest in him, leading to a potential overwhelming of his emotions by her affection. Yozo regrets his prior vulnerability and intimacy with her.

However, one evening, while Yozo and Horiki are out drinking and find themselves short on money, Yozo decides to take Horiki to the café where Tsuneko works, knowing she would provide them with complimentary drinks. On their way there, Horiki shares his intentions of kissing whoever serves them, expressing his yearning for female companionship. Upon arrival, Yozo finds himself in an uncomfortable situation. A waitress he does not recognize sits next to him, with Tsuneko beside Horiki. At that moment, Yozo is struck by the awkward realization that he will have to witness Horiki kissing Tsuneko. He reflects that his discomfiture is not due to possessiveness, but rather a deep empathy for Tsuneko. Yozo anticipates that she will feel obligated to let Horiki kiss her while he, Yozo, watches, assuming this might lead her to sever ties with him.

Yozo readies himself, expecting Horiki to make a move and kiss Tsuneko. However, Yozo is surprised when Horiki remarks that he would never engage with someone who appears so poverty-stricken. Hearing this, an overpowering urge to drown his emotions in alcohol washes over Yozo, prompting him to request Tsuneko to fetch more drinks. He feels a sense of embarrassment that even in his inebriated and absurd state, Horiki refrains from making a move on Tsuneko. As he gazes at Tsuneko, he acknowledges that Horiki’s observation is accurate – she exudes an aura of destitution and sorrow. Paradoxically, this intensifies Yozo’s empathy for her, as if they share a deep connection. For the very first time in his entire life, Yozo feels like has fallen in love. His response to this overwhelming emotion is to vomit and lose consciousness.

Upon awakening, Yozo finds himself in Tsuneko’s apartment. She lies beside him, expressing her profound unhappiness and despair. Her sentiments strike a chord with Yozo, who shares the feeling of being utterly drained by life. He believes he can no longer endure the struggles of existence, and when Tsuneko proposes that they both end their lives, Yozo readily agrees.

Throughout that day, Yozo and Tsuneko wander through the city. While Yozo has committed to the idea of ending his life alongside Tsuneko, he has not fully comprehended the gravity of his decision. However, when he attempts to pay for a glass of milk and realizes he possesses only three coins, a wave of terror engulfs him. He also realizes that his only possessions happen to be the coat and kimono he currently wears. It is at that moment that he grasps the stark reality that he cannot persist any longer; he believes he must end his life. That night, he and Tsuneko carry out their plan to end their lives. Yozo follows through with their decision, and they jump together into the sea. Tragically, however, Yozo survives but Tsuneko does not.

The news of Yozo’s unsuccessful suicide attempt spreads across Japan owing to his father’s prominent political status. Yozo is admitted to a hospital, where a relative visits him. They convey that his father and the rest of his immediate family are livid and contemplating disowning him. However, Yozo remains apathetic to their anger; his thoughts are consumed by grief as he mourns the death of Tsuneko, realizing that she is the sole person he has loved.

Following his hospitalization, Yozo faces charges of being an accomplice to a suicide. He is brought to the police station, but due to the lingering effects of the water in his lungs from his suicide attempt, he is not placed in a cell with other inmates. In the middle of the night, an elderly guard escorts him from the cell for interrogation. Yozo quickly discerns that the guard holds little real authority; he appears bored and seems to be merely passing the time. Yozo decides to cooperate and offers a detailed but deliberately inaccurate confession about the incident, which notably pleases the guard.

The following day, Yozo meets with the police chief, who is notably less intense than the guard. The chief comments on Yozo’s handsome appearance and informs him that the district attorney will determine whether to press charges. He advises Yozo to take care of his health due to his persistent cough. At one point, Yozo coughs into a handkerchief that already bears bloodstains from a pimple. The chief mistakenly assumes that Yozo is coughing up blood, and Yozo decides to play along, allowing the chief to believe he is in worse condition than he truly is.

The police chief instructs Yozo to contact a guarantor, and Yozo reaches out to a man from his hometown known as Flatfish. Flatfish agrees to meet Yozo in the nearby city of Yokohama, where he faces examination by the district attorney. Yozo underestimates the district attorney, perceiving him as straightforward and uncomplicated. He exaggerates his cough in the same manner as he did in front of the police chief. However, the district attorney surprises him with a smile and a probing question: “Was that real?” At that moment, Yozo is transported back to the day when Takeichi accused him of purposefully falling at school.

Yozo finds himself in a state where he would prefer spending a decade in prison over enduring another interaction like the one he just had with the district attorney. Nevertheless, the district attorney ultimately dismisses the charges, though this outcome fails to bring any happiness to Yozo.

The Third Notebook – Summary

Yozo is expelled from college due to his association with Tsuneko’s suicide. He spends his days at Flatfish’s residence, even though his family maintains no direct contact with him. However, it becomes apparent to Yozo that his brothers periodically send small sums of money to Flatfish. Flatfish, concerned that Yozo might attempt suicide again, forbids him from leaving the house. Yozo, though, is too drained to entertain such thoughts. Nonetheless, he longs for alcohol and cigarettes, which are among the few things in life he misses.

One evening, Flatfish invites Yozo to join him and his son for dinner downstairs. It turns out to be a pleasant meal. However, the atmosphere changes when Flatfish begins to inquire about Yozo’s future aspirations and plans. Flatfish expresses his willingness to assist Yozo in embarking on a more purposeful path if Yozo would only share his desires. Yozo, however, feels utterly incapable of responding. He lacks clarity about his aspirations and is equally uncertain about what Flatfish envisions for him. Yozo secretly wishes Flatfish would straightforwardly advise him, such as suggesting he enroll in school for the upcoming spring term. Presently, he remains unable to articulate his thoughts, much to Flatfish’s growing frustration.

When Yozo expresses his desire to pursue a career as a painter, Flatfish’s reaction is incredulous. He laughs mockingly and regards Yozo with a scornful look, which, for Yozo, conveys the worst, most disheartening aspects of adulthood. The following day, Yozo decides to leave Flatfish’s house, not out of embarrassment over their conversation, but rather to avoid further burdening him. He leaves a note explaining that he’s headed to Horiki’s house, assuring Flatfish that there is no need to worry.

In reality, Yozo has no intention of going to Horiki’s house. As he wanders through the city, he finds himself with nowhere else to go and ends up at Horiki’s place anyway. Horiki greets him with indifference and disdain. While Yozo is there, a woman arrives to visit Horiki. She works for a magazine that commissioned an illustration from him and wants to have a private conversation with him. An unexpected telegram arrives from Flatfish, prompting an angry inquiry from Horiki about what kind of trouble Yozo has brought upon him. Horiki insists that Yozo returns to Flatfish immediately, refusing to be associated with any potential scandal.

The woman from the magazine, named Shizuko, offers to take Yozo home with her. She lives alone with her five-year-old daughter, Shigeko, as her husband passed away a few years ago. She is drawn to Yozo’s melancholy demeanor and praises him for his sensitivity. Yozo begins to live with Shizuko and her daughter, essentially becoming a “kept man.” Initially, he does not do much besides spending time with Shigeko, occasionally observing a tattered kite entangled in telephone wires outside the window. The sight of the kite brings a smile to his face as he watches it flutter in the wind, seemingly going nowhere.

Yozo’s depression deepens to the point where Shizuko arranges a meeting with him, Flatfish, and Horiki. They collectively decide that Yozo should sever ties with his family and marry Shizuko. Meanwhile, Yozo’s cartoons gained significant popularity, providing him with enough income to indulge in alcohol and cigarettes.

He believes he has established a reasonably close relationship with young Shigeko, but one day, she unintentionally wounds him deeply by casually expressing her longing for her “real” father. Yozo realizes that once again, he had let his guard down, only to be hurt by an unexpected remark.

In these times, Horiki starts speaking to Yozo in an incredibly condescending manner. This change in attitude arises from his participation in the meeting concerning Yozo’s future, leading him to view himself as something of an authority figure in their relationship. He instructs Yozo on how to conform to societal norms, discussing what is considered acceptable in society. This comment prompts Yozo to ponder the concept of society itself—what exactly is society? He surmises that it must be the “plural of human beings.” Throughout his life, he has contemplated society’s standards and approval, but now he begins to perceive society as more than just a collection of individuals. In his view, society represents an individual entity.

Once Yozo begins conceptualizing society as an individual entity, his usual shyness and apprehension lessen somewhat. He becomes more capable of pursuing his desires, but this transformation does not lead to happiness. On the contrary, he finds himself trapped in a profound state of depression. He spends his days creating silly and purposeless cartoons for various magazines that now pay for his work. In the evenings, he seeks solace in heavy drinking, returning home late and often speaking rudely to Shizuko, though she remains composed and refuses to be provoked by his behavior. Recognizing that Shizuko and Shigeko would be better off without him, Yozo eventually decides to leave for good.

After parting ways with Shizuko, Yozo frequents a bar in the Kyobashi neighborhood, where he informs the bar manager that he left Shizuko for her. This simple statement secures him a place at the bar and lodging in the upstairs apartment. A year passes, during which Yozo continues to battle his fear of human interaction while consuming copious amounts of alcohol. Concurrently, he produces cartoons for various magazines, some of which delve into pornographic themes. However, his life takes a different turn when a seventeen-year-old woman named Yoshiko attempts to persuade him to quit drinking. She works at a tobacco store across the street from the bar.

When Yoshiko implores Yozo to stop drinking, he fails to comprehend why he should make such a change. He expresses his desire to kiss her, and she does not object to the idea. Shortly after this, while walking home intoxicated one night, Yozo falls into a manhole. Yoshiko helps rescue him and tends to his injuries, once again emphasizing that he drinks excessively. In a somewhat playful manner, he declares that starting from the next day, he will abstain from alcohol, but only if Yoshiko agrees to marry him. It is meant as a jest, but to his surprise, she agrees, and they make plans to marry, contingent on Yozo’s commitment to sobriety.

The following day, Yozo succumbs to alcohol once again. He attempts to inform Yoshiko that their agreement should be called off because he is drunk, but she refuses to believe him, convinced that he will not break his promise. Despite his insistence that he is intoxicated and unworthy of kissing her, she remains steadfast in her faith. Suddenly, Yozo is struck by the fact that Yoshiko is a virgin, and he decides on the spot that he will marry her, driven by his curiosity. They proceed to get married shortly afterward. Yozo does not experience much happiness, and he soon realizes that the decision to marry brings him profound suffering.

The Third Notebook: Part Two – Summary

Yozo and Yoshiko move into an apartment together, and Yozo successfully refrains from drinking. He finds joy in spending time with his new wife and begins to harbor hope that he can attain happiness and lead a normal life. However, Horiki resurfaces in his life, announcing in front of Yoshiko that Shizuko has requested Yozo’s visit. This news triggers deep shame in Yozo regarding his past actions and abandonment of Shizuko. Troubled by these emotions, he proposes to Horiki that they go out for a drink. Subsequently, Yozo and Horiki establish a pattern of periodic visits to the bar in Kyobashi, where they indulge in heavy drinking before visiting Shizuko, sometimes even spending the night at her apartment.

On one occasion, Horiki approaches Yozo for a loan. Yozo sends Yoshiko to a pawnshop to sell some of her clothes and instructs her to use a portion of the money to purchase gin. Yozo and Horiki spend the evening drinking on the rooftop, growing increasingly intoxicated. Their conversation shifts towards criminal activities, and Horiki makes offensive remarks about how he has never been arrested or imprisoned, unlike Yozo. He also mentions that he does not desire the death of women, alluding to Yozo’s past with Tsuneko. Yozo recognizes this as a rude comment but refrains from defending himself because he has become accustomed to viewing himself as “evil.”

While on the rooftop, Horiki suddenly declares that he is hungry and descends the stairs to look for food. However, he swiftly returns with an unusual expression on his face, prompting Yozo to join him downstairs to see what is happening. There, they discover a man violating Yoshiko in another room. Yozo is deeply troubled by this sight but remains passive, attempting to rationalize the situation as “just another aspect of the behavior of human beings.” Horiki, on the other hand, decides to leave. Yozo returns to his gin and tears, while Yoshiko eventually appears and offers him some food, explaining that the man who raped her had promised not to harm her.

Before departing, Horiki instructed Yozo to “forgive” Yoshiko, but Yozo finds himself unable to both forgive or blame her for what occurred. His primary concern is not that she was a victim but that she was exploited due to her trusting nature. In the ensuing days and weeks, Yoshiko becomes jittery and anxious around Yozo, constantly worrying about his feelings. In response, Yozo immerses himself deeper into his drinking.

One night, Yozo returns home in an excruciatingly drunken state. While seeking some sugared water before bed, he stumbles upon a box of sleeping pills. Unaware of what he is taking, he consumes all of them before retiring to bed. Yozo remains unconscious for three days, and the doctor who treats him classifies the incident as an accident, sparing him from police involvement upon waking.

When Yozo regains consciousness, Flatfish is present. He engages in a conversation with the bar’s Madam, noting that Yozo’s previous suicide attempt also occurred near the end of the year. In a confused state, Yozo asks to be separated from Yoshiko and vaguely mentions going to a place devoid of women, without fully comprehending his own words.

Following the sleeping pill incident, Yoshiko believes Yozo tried to end his life because he holds himself responsible for her assault. Flatfish provides Yozo with some money, pretending it is a gift from himself, although Yozo knows it comes from his brothers. Yozo decides to use the money for a solo trip to some hot springs, but the excursion brings him no solace. He spends the entire time drinking indoors, ruminating on Yoshiko, and sinking deeper into his misery. His return to Tokyo only amplifies his despair.

One night, in a drunken haze, Yozo vomits blood and collapses into a snowdrift. Struggling to his feet, he enters a pharmacy in search of medication. Despite the late hour, the female proprietor of the pharmacy is still on duty. Upon seeing Yozo, they both immediately sense a shared understanding of their respective suffering. Tears well up in both of their eyes, prompting Yozo to retreat and return to his apartment.

The following night, Yozo revisits the pharmacy and confides in the pharmacist about his condition. She advises him to abstain from alcohol, sharing that her husband’s life was prematurely shortened due to excessive drinking. Yozo, however, explains his discomfort when sober. In response, the pharmacist provides him with medication to alleviate his restlessness and extract a commitment from him not to consume alcohol.

The medicine prescribed to Yozo turns out to be morphine. Initially, he perceives it as a viable alternative to alcohol. Morphine induces a sense of optimism and tranquility, dispelling his anxieties and frequently elevating his mood. However, Yozo soon falls into the pattern of taking multiple daily injections of morphine. As his supply dwindles, he returns to the pharmacy, where the pharmacist is initially hesitant to provide more but eventually acquiesces. This cycle repeats, and Yozo develops an affair with the elderly pharmacist, enabling him to continue his access to, and consumption of the drug.

Yozo finds himself thoroughly addicted to morphine, realizing its grip on him is no different than that of alcohol. Although he harbors a desire to end his life, he continues to frequent the pharmacy for morphine, accumulating substantial debt. Desperate, he decides to compose a letter to his father, pleading for assistance and vowing to take his own life if help does not arrive. However, his father never responds.

On the day Yozo plans to carry out his suicide, Horiki, and Flatfish unexpectedly appear, whisking him away to a psychiatric ward. Yoshiko accompanies them, attempting to surreptitiously provide Yozo with morphine, believing he may need it. Nevertheless, Yozo refrains from taking the drug.

In the psychiatric ward, Yozo comes to the sobering realization that his earlier premonition has materialized: he now resides in an environment devoid of women. Furthermore, he acknowledges that even upon leaving the ward, society will forever label him a “reject.” He believes he has been permanently disqualified from being considered a human being.

After spending three months in the psychiatric facility, Yozo is discharged. His older brother and Flatfish arrive to collect him, bearing the news of their father’s death. Yozo’s family offers financial support without prying into his past, on the condition that he departs from Tokyo. Grief-stricken by his father’s death, Yozo consents to leaving the city. His brother arranges for him to stay in a house near a coastal hot spring.

Three years have now elapsed since Yozo’s relocation to the countryside. Occasional bouts of coughing up blood persist, and the eccentric old servant hired by his brother occasionally subjects him to peculiar torments. For instance, once tasked with acquiring sleeping pills she mistakenly procured laxatives instead. Yozo consumed ten of the pills and had to endure a sleepless night with aching stomach cramps. However, in the grand scheme of things, he neither experiences happiness nor sorrow; life simply drifts past him. Approaching twenty-seven years of age, his hair has already started to gray, and most would perceive him as older than forty.

Epilogue

The voice of the unnamed narrator of the Prologue re-emerges, explaining that he never had the chance to meet the “madman” responsible for writing these notebooks, referring to Yozo. However, he did have a connection with the bartender who managed the bar in Kyobashi, a person Yozo frequently mentions in his notebooks. The speaker visited her bar in the year 1935, approximately five years after the events detailed in Yozo’s writings. During his current visit to the countryside to see a friend and acquire seafood for his family, he stumbles upon a café where he recognizes the woman working there as the same bartender from Kyobashi. Striking up a conversation, she inquires whether he knew Yozo.

The unnamed speaker informs the bartender that he never met Yozo, yet she insists on giving him three of Yozo’s notebooks, suggesting they might provide material for a compelling novel. Initially, the speaker considers returning them, but the three accompanying pictures of Yozo pique his curiosity. That evening, intoxicated with his friend, he decides to spend the night staying awake, engrossed in reading all of Yozo’s notebooks.

The unnamed speaker decides to publish Yozo’s notebooks exactly as they are, without making any alterations. The following day, he revisits the café and has a conversation with the bartender from Kyobashi about the notebooks. She reveals that she received these notebooks in the mail about ten years ago. Although she believes they were sent by Yozo, there was no return address included. When the speaker inquires whether she shed tears while reading them, she responds in the negative. Instead, she reflects on how, when individuals reach such a state, they become incapable of anything useful. Nevertheless, she holds fond memories of Yozo and insists that, despite everything, he was a “good boy” and an “angel.”