Chief Seattle’s Speech, also known as the Treaty Oration of 1854 is a remarkable speech which presents us a perspective that has for long been replaced by a Western idea of ‘civilization’. It is an eloquent expression of the untold sufferings inflicted on the natives of places all around the world at the hands of European colonizers. The Chief however does not present the case of his tribe with bitterness but rather seems to embrace the situation with the wisdom which accepts the transience of all things. The piece also gives us a view of the ethos and culture on which Seattle’s tribe had been built on. And it is in every way as important and dear as the ideas of a Western version of “civilization” propagated by the White Man. Chief Seattle’s speech is imbued with the themes of tolerance, ecological conservation, race, reconciliation, brotherhood, and mutual respect of different ways of living.

Furthermore, this speech is a translation of what was actually spoken and is probably a product of a two-step translation process as it was articulated in the Lushootseed language spoken by the Chief, mediated via the Chinook Indian trade language before finally being translated to English. For a greater understanding of the text, read the historical background for Chief Seattle’s speech by clicking this link : Chief Seattle’s Speech Background.

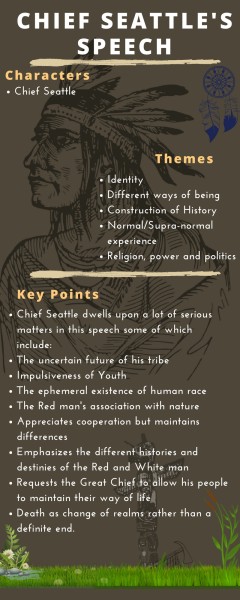

Chief Seattle’s Speech | Summary

Chief Seattle begins the oration on a dreary note as he senses an imminent danger which has cast its shadow over the existence of his people. The existence his tribe has become shrouded by uncertainty. The European colonizers have occupied their lands, massacred many and now offer a proposal to ‘buy’ the lands of his tribe and consign them to a small reservation. It is in such a context that the Chef is making his speech. The sky which had seemed eternal and unchanging no longer commands the permanence it used to:

“Today is fair tomorrow it may be overcast with clouds.”

Chief Seattle then proceeds by saying that his words are unchangeable like the stars and the Chief in Washington can rely on them with the same certainty with which he expects the rising of the sun and the return of the seasons. He understands that his tribe is vastly outnumbered by the white settlers and that the present and the future of his people looks bleak. He however express this ominous view by reminding the White Man that his people have been living in the place for “centuries untold” and that they have had a rich history and culture which pre-dates the time when the White Man set his foot upon the land.

He says his people no longer need the vast stretches of land they lived in as they have dwindled in numbers. Once, they covered the land ” as the waves of a wind-ruffled sea cover its shell-paved floor “. Now, however, they can easily fit in the reservation (areas demarcated by the government) allocated them by the White invaders. Though he says he “doesn’t reproach (his) paleface brothers for hastening” the decline of his people , the speech provides glimpses of atrocities the White Man inflicted on the natives : of how the settlers began pushing his tribe westward and how the Red man is frozen with fear whenever he hears “the approaching footsteps of his fell destroyer”.

In the third paragraph, the Chief highlights the violent effects arising from the impulsiveness of youth. The wisdom laden lines of the Chief, spoken centuries ago , seem to find its relevance even in the 21st century :

“Revenge by young men is considered gain even at the cost of their own lives, but old men who stayed at home in times of war and mothers who have sons to lose, know better.”

It seems that his tribe has lost a huge portion of its youth while trying to fight the injustice meted out against them. The Chief seems to have witnessed a lot of bloodshed and doesn’t want to see the cycle of violence repeating anymore.

He says that the Washington Chief’s promise of protection in case his tribe agrees to hand over their lands is a generous one. The Chief’s Squamish tribe had often been in conflict with the Haida and Tsimshian tribes to the north and Seattle appreciates the Washington Chief’s offer of protection against their traditional enemies. Yet, there’s a limit to which the Red and the White man can get along for they are separate races having separate destinies and even if they were to share the same heavenly father, he seems to be a biased one :

“If we have a common Heavenly Father, he must be partial, for He came to his paleface children. We never saw him…No; we are two distinct races with separate origins and destinies. There is little in common between us.”

Seattle then highlights how divergent are the value systems of the two races. He contrasts how the graves of their forefathers are sacred to them whereas the White man seems to actively avoid the tombs of his people. The religion of the White man is based on scriptures, written on tablets of stone whereas the Red Man’s religion is based on oral tradition, written in the hearts of his people. Furthermore, the deceased of the White man seem to forever depart form the earth whereas the deceased of the Red Man love their land and their people and return to their home as guiding spirits.

The contrast intensifies in the next few paragraphs where the Chief states ” Day and Night cannot dwell together” and describes how the Red Man has fled the White Man “as the morning mist flees the morning sun”. Their fate is sealed and their days are numbered. However, the Chief doesn’t accept this fate in bitterness but acknowledges the universal fact that tribes replace tribes, and nations replace nations, like the waves of the sea. A common ruin awaits all and it is futile to regret over what destiny has in store for us. Though the White Man has conquered most of their lands for now, his time will surely come.

Before ending his speech Chief Seattle places one condition before the Washington Chief :

But should we accept it, I here and now make this the first condition: That we will not be denied the privilege, without molestation, of visiting at will the graves of our ancestors and friends.

He asserts that in the distant future, when the White Man thinks the silent streets at night are empty at night, it will indeed throng with the presence of the returning natives “who once filled them and still love the beautiful land”.

Underlying his assertion, we are accosted with a worldview that is once mysterious and familiar:

“Dead did I say? There is no death . Only a change of worlds”

For an in-depth critical analysis of Chief Seattle’s Treaty Oration click here.